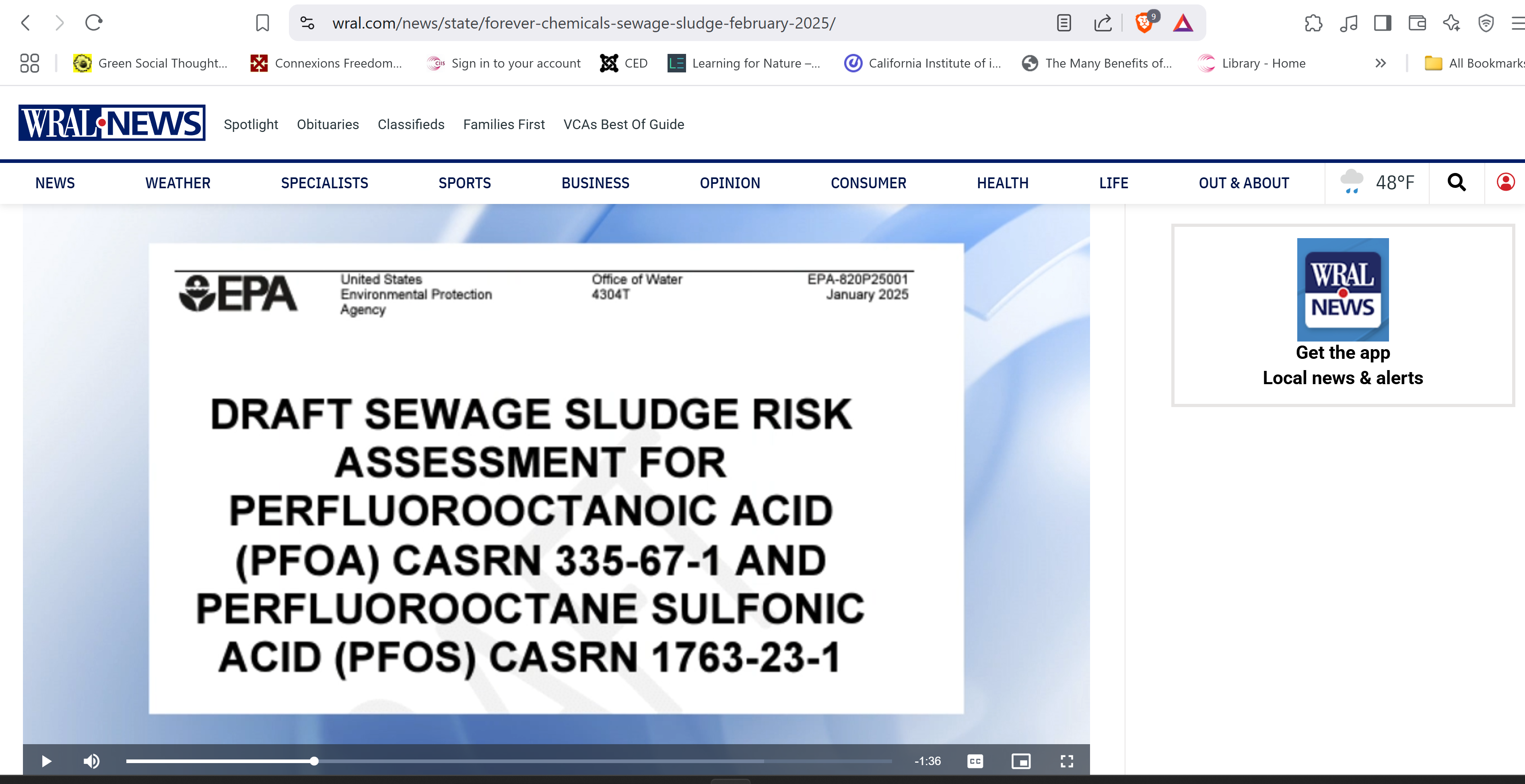

PFAS Contaminated Sewage Sludge Fertilizers Can Cause Cancer and Other Diseases – US EPA

The EPA recently released a long-awaited draft report demonstrating that toxic “forever chemicals” in sewage sludge applied to farmland can cause cancer and other diseases in people who live near farm fields where the sludge is applied, or consume tainted milk, beef or other foods from these farms.

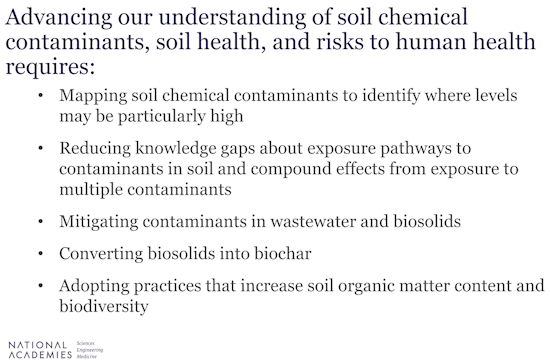

The chemicals – per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – contaminate wastewater treatment plant sludge that for decades, at EPA’s urging, has been applied as cheap fertilizer to many millions of acres of pasture and cropland. PFAS are taken up by crops and grasses grown on contaminated land, accumulate in the meat and milk of pasture-raised livestock, and pollute the drinking water of at least 45% of Americans. Testing by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that nearly everyone in the U.S. has one or more PFAS in their bloodstreams.

read full article at Sustainable Pulse

Anti-sludge signs dotted the roadsides of rural Newton and McDonald Counties on Feb. 24 (Athena Fosler-Brazil/Missourian).

Anti-sludge signs dotted the roadsides of rural Newton and McDonald Counties on Feb. 24 (Athena Fosler-Brazil/Missourian).

A field in Texas where sludge-based fertilizer had been applied. Neighbors claim it led to animal deaths.Credit...Jordan Vonderhaar for The New York Times

A field in Texas where sludge-based fertilizer had been applied. Neighbors claim it led to animal deaths.Credit...Jordan Vonderhaar for The New York Times

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: CHRIS GRIGGS/CONSUMER REPORTS, GETTY IMAGES

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: CHRIS GRIGGS/CONSUMER REPORTS, GETTY IMAGES